TOPICS

Filter topic

New economics is the study of human behaviour in social groups – influenced by culture, location and history – in pursuit of monetary gain. It emphasises institutions, uncertainty, altruism, diversity and ethics. It recognises consumer diversity, economics of specialisation and scale, uncertainty, bounded rationality, inherent technological change and the endogeneity of money as critical elements. It is distinguished from the old economics characterised by equilibrium, representative agents, certainty equivalence and determinism.

For further reading, other websites promoting new economics include:

- New Economics Foundation (NEF)

- Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET)

- New Economics for Women (NEW)

- New Economy Coalition supporting USA sustainability

- Frans Doorman, sociologist, New-Economics

- Schumacher Center for a new economics

- Levy Economics Institute, New York State

- Institute for International Political Economy (IPE) Berlin

- Greenwich Political Economy Research Centre

- The New School for Social Research, New York

- Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts, Amherst

- Cambridge Political Economy Society

- New Economics papers on Academia.edu

- Post-Keynesian Economics Society

- Econation for people and planet (a New Zealand site)

- Rethinking Economics

“Towards New Thinking in Economics: Terry Backer on structural macroeconomics, climate change mitigation, the relevance of empirical evidence, and the need for a revised economics discipline”

“Spatially Rebalancing the UK Economy: Towards a New Policy Model?” – Martin et al., 2015

“Critical Survey. The new ‘geographical’ turn in economics: some critical reflections” – Martin, 1999

Arestis, P. and González-Martinez, A. (2015) “The Absence of Environmental Issues in the New Consensus Macroeconomics is only One of Numerous Criticisms”, in P. Arestis Sawyer (eds), Finance and the Macroeconomics Environmental Policies, Annual Edition International Papers in Political Economy, Palgrave Macmillan. Available on Springer.

Coyle. D. (2019) Homo Economicus, AIs, humans and rats: decision-making and economic welfare, Journal of Economic Methodology, 26:1, 2-12, doi:10.1080/1350178X.2018.1527135

Martin, R., Pike, A., Tyler, P. and Gardiner, B. (2016) Spatially Rebalancing the UK Economy: Towards a New Policy Model? Regional Studies, 50, 342-357, doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1118450

Martin, R. (1999) Critical Survey. The new ‘geographical turn’ in economics: some critical reflections. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 23, 65-91. Available on JSTOR.

An economic system is an interacting dynamic system of consumption and (derived) production, and the trade of goods and services, based on an institutional framework of norms and laws. Today the mixed market-based economic system has become globalised through international trade and the internet. Examples of a different system are the planned economies of North Korea or the former Soviet Union.

Barker, T. (2011) “A ‘whole systems’ approach in ecological economics”, in Simon Dietz, Jonathan Michie and Christine Oughton (eds), The Political Economy of the Environment, Routledge. Available on Taylor & Francis.

A whole-systems approach argues that the behaviour of a system cannot be understood by focusing on the behaviour of its individual components alone. Interaction/s between components leads to outcomes at the system level that differ, in some cases diametrically, from the behaviour of individual components.

Classic examples of such systems effects include Keynesian unemployment (Keynes, 1936) in which individual firms faced with a loss in demand reduce their employment, so that demand falls further. Other examples are the ‘tragedy of the commons’ (Hardin, 1968, 1998) and lock-in to inefficient technologies (David, 1985).

The whole-systems approach recognises that interaction between individual components, the dynamics, and the feedback effects are all part of the complexity of systems-level analysis.

“A ‘whole systems’ approach in ecological economics” – Barker, 2011

Barker, T. (2011) “A ‘whole systems’ approach in ecological economics”, in Simon Dietz, Jonathan Michie and Christine Oughton (eds), The Political Economy of the Environment, 99-114. Available on Research Gate.

David, P. (1985) Clio and the Economics of QWERTY, The American Economic Review, 75:2, 332-337. Available on JSTOR.

Hardin, G. (1968) The Tragedy of the Commons, Science, 162:3859, 1243-1248, DOI: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

Hardin, G. (1998) Extensions of “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Science, 280:5364, 682 – 683, DOI: 10.1126/science.280.5364.682.

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, London: Macmillan Press. Available on JSTOR.

The energy and climate systems have been influential in affecting economic thinking over time. Limits of natural resources, such as oil reserves or the climate’s carrying capacities, as well as human resources, have created a debate on limiting economic growth. Moreover, the economic crises in the 1970s have challenged the validity of assuming a stable relationship between inflation and unemployment.

In economic theory, this led to macroeconomic theory and modelling based on micro‐economic foundations, rejecting the Keynesian Revolution. However, the climate crisis and especially the 2008 global financial crisis, have led to further challenges to the basic assumptions of the neoclassical consensus, such as whether these micro foundations are valid, the existence of equilibrium, the separation of monetary and fiscal policy, and the economy as a closed system.

The economy is an open system, integrated with those involving energy and the environment, requiring E3 approaches for robust consideration of economic management and policies.

“Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, and Mill: The forerunners of limits to growth” – Zweig, 1979

“Climate change and social vulnerability: toward a sociology and geography of food insecurity” – Bohle et al., 1994

“The role of natural resources in economic development” – Barbier, 2012

“Reacting to the Lucas Critique: The Keynesians’ Pragmatic Replies” – Goutsmedt et al., 2017

Zweig, K. (1979) Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, and Mill: The forerunners of limits to growth, Futures, 11:6, 510‐523. Available on Elsevier.

Barbier, E. (2012) “The role of natural resources in economic development”, in Anderson K. (Ed.), Australia’s Economy in its International Context: The Joseph Fisher Lectures, Volume 2: 1956‐2012. South Australia: University of Adelaide Press. Available on JSTOR.

Goutsmedt, A., Pinzón‐Fuchs, E., Renault, M. and Sergi, F (2017) Reacting to the Lucas Critique: The Keynesians’ Pragmatic Replies. Available on SSRN.

Bohle, H.G., Downing, T.E., and Watts, M.J. (1994) Climate change and social vulnerability: toward a sociology and geography of food insecurity, Global Environmental Change, 4:1, 37-48. Available on Elsevier.

Economic externalities are effects from an economic activity affecting other people’s wellbeing – usually elsewhere and subsequent to the activity itself. The effects occur later through physical processes, e.g., air and sea pollution are spread wider than the original activity. Externalities are all pervasive and have cumulative impacts on people, animals, vegetation, buildings and other infrastructure, now and in the future.

They can be negative or positive:

- A negative externality is when the cost to a person or institution of their activity or decision is less than the social cost, taking account of the impacts on others. For example, the emission of harmful exhaust gases from vehicle use.

- A positive externality is when the action or decision provides a social benefit. For example, returning pasture to forestry. Institutions make use of, manage, or capture beneficial externalities where possible or viable. Organisations, such as a hotel in a particularly attractive location, can provide and market services based on the externalities.

Interdisciplinarity is the bringing together of several disciplines in order to study a question of interest. Economics is a social science, and hence intrinsically interdisciplinary: theorists & practitioners should, as scientists, acknowledge that social issues involve all the social sciences, especially political science and sociology. Further, the sub-disciplines of economic geography and economic history can be critical for a wider understanding of central economic issues such as inequality, underemployment and Brexit.

Mitigation of climate change, in particular, involves engineering, economics, social psychology, politics and law.

Centre for Business Research, Cambridge

“An interdisciplinary model for macroeconomics” – Haldane and Turrell, 2019

Haldane, A. G. and Turrell, A. E. (2018) An interdisciplinary model for macroeconomics. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34:1-2, 219-251. Available on Oxford Academic.

Complexity economics is the study of economic systems as complex systems. Both concepts are closely related to the ‘whole systems’ section above.

The following challenges for complexity economics are summarised from the website Exploring-economics.

(1) Is this a new field or a tool for understanding and explanation, like mathematics?

(2) What is the role of mathematics?

(3) How complex should the models be in order to provide understanding? Humans are far more complex than can be modelled, hence radical simplification is inevitable, e.g. agent-based modelling where the agents adopt simple rules.

(4) How should agent-based models be replicated and validated? Should they explain stylised facts? Clearly there is a trade-off between simplicity of explanation and the matching with economic observations.

“Towards a new complexity economics for sustainability” – Foxon et al., 2013

“How to relate models to reality? An epistemological framework for the validation and verification of computational models” – Gräbner, 2017

Beinhocker, E. D. (2006) The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press. Available on Google Books.

Foxon, T, Köhler, J., Michie, J. and Oughton, C. (2013) Towards a new complexity economics for sustainability, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 37:1, 187–208. Available on Oxford Academic.

Gräbner, C. (2017) How to relate models to reality? An epistemological framework for the validation and verification of computational models (No. 63). ICAE Working Paper Series. PDF available here.

Kirman, A. (2016) Complexity and Economic Policy: A Paradigm Shift or a Change in Perspective? A Review Essay on David Colander and Roland Kupers’s ‘Complexity and the Art of Public Policy’, Journal of Economic Literature, 54:2, 534-572. Available on American Economics Association.

The Wikipedia definition is excellent: globalisation is the process of interaction and integration between people, companies, and governments worldwide. The International Monetary Fund (2000) identified four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital movements and investment, migration of people and the dissemination of knowledge. Global heating and the financial crisis of 2008 are both global phenomena.

“Forms of globalisation: from ‘capitalism unleashed’ to a global green new deal” – Mitchie, 2018

“Beyond peak emission transfers: historical impacts of globalisation and future impacts of climate policies on international emissions transfers” – Wood et al., 2019

International Monetary Fund (2000) Globalization: Threat or Opportunity?, IMF Publications.

Michie, J. (2018). Forms of globalisation: from ‘capitalism unleashed’ to a global green new deal, European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies, 15:2, 163-173. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4337/ejeep.2018.02.08

Justice has always attracted as much serious attention as utility in the theory of ethics. Economics is not ethics-free: “…basing economics on the ethics of individuals assumed to be entirely self-interested can go badly wrong, and that ‘willingness to pay’ is invalid as a means of valuation” (Broome, 2008).

Social justice is proposed in Rawls’ theories of justice and fairness (1971, 2001). His principles of justice are:

(1) “Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all”; and

(2) “Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: first, they are to be attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle).”

Broome, J. (2008) “Why Economics Needs Ethical Theory”, in Kaushik Basu and Ravi Kanbur (eds.), Welfare, Development, Philosophy and Social Science: Essays for Amartya Sen’s 75th birthday, Oxford: Oxford University Press. PDF available here.

Murphy, R. (2015) “The Joy of Tax. How a fair tax system can create a better society”, Random House, ISBN: 1473525330, 9781473525337. Available on Google Books.

Consider two population groups: a well-off urban majority burning fossil fuels, and a subsistence rural minority in danger of losing access to food and water if the climate changes. There is a triple injustice in climate change:

- The rural minority has not been responsible for the greenhouse gas concentrations causing climate change, nor has it benefited from the comfort & power provided by fossil energy services.

- The rural minority will suffer the most from climate change because of droughts & floods, and it cannot buy its way out of the problem.

- The cost-benefit neoclassical approach to the problem sets aside the equity aspect and under-represents the harm caused to low-income subsistence minority in its proposed policies.

“Climate change, social justice and development” – Barker et al., 2008

“Pushing the boundaries of climate economics: critical issues to consider in climate policy analysis”- Scrieciu et al., 2011

“A new economics approach to modelling policies to achieve global 2020 targets for climate stabilisation” – Barker et al., 2011

“The economic feasibility of policies for decarbonisation” – Barker et al., 2014

“GDP and employment effects of policies to close the 2020 emissions gap” – Barker et al., 2015

“The economics of avoiding dangerous climate change” – Barker, 2017

“The world as it is: a vision for a social science (and policy) turn in climate justice” – Storey, 2019

“Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality” – Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, 2019

Economic inequality is now recognised as a major problem in many economies, including regional economies (Arestis at al., 2011; Milanovic, 2017). Although global inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient on real incomes, has generally fallen over the last few decades, this is largely due to the rapid increases in incomes in China and other newly industrialised countries. Within country inequalities have generally increased, especially for the very rich compared to others.

The causes are many, and are inter-related. They include deregulation, reductions in high rates of taxation, financialisation (both international and national), tax avoidance (IMF, 2019), rent-seeking by the rich, as well as being an intrinsic feature of capitalism (Piketty, 2014) where nominal wealth grows faster than nominal income.

The effects are mostly deleterious for society and the economy (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009). Proposed solutions are wealth taxes (Wolff, 2017), higher top-rate income taxes, reform of the taxation of international corporations on to a country-by-country basis, a financial transactions tax, and re-regulation.

James Galbraith’s Inequality Project

“Importance of tackling income inequality and relevant economic policies” – Arestis, 2018

“Productivity and inequality in the UK: a political economy perspective” – Arestis, 2020

“UK and other advanced economies productivity and income inequality” – Arestis, 2020

Arestis, P., Martin, R. and Tyler, P. (2011) The persistence of inequality? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 4, 3-11. DOI:doi:10.1093/cjres/rsr001.

Wilkinson, R. G. and Pickett, K. (2009) The spirit level: why more equal societies almost always do better, London: Allen Lane. ISBN: 9781846140396. Available on Research Gate.

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap Press, ISBN: 067443000X. Available on De Gruyter.

Milanovic, B. (2016) Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Available on Springer.

Wolff, E. N. (2017) A Century of Wealth in America, Belknap Press, ISBN: 9780674495142. Available on Google Books.

International Monetary Fund (2019) Finance and Development: Hidden Corners of the Global Economy, IMF Publications.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) says gender equality “means that women and men, and girls and boys, enjoy the same rights, resources, opportunities and protections.” Gender equality is one of the sustainable development goals of the United Nations.

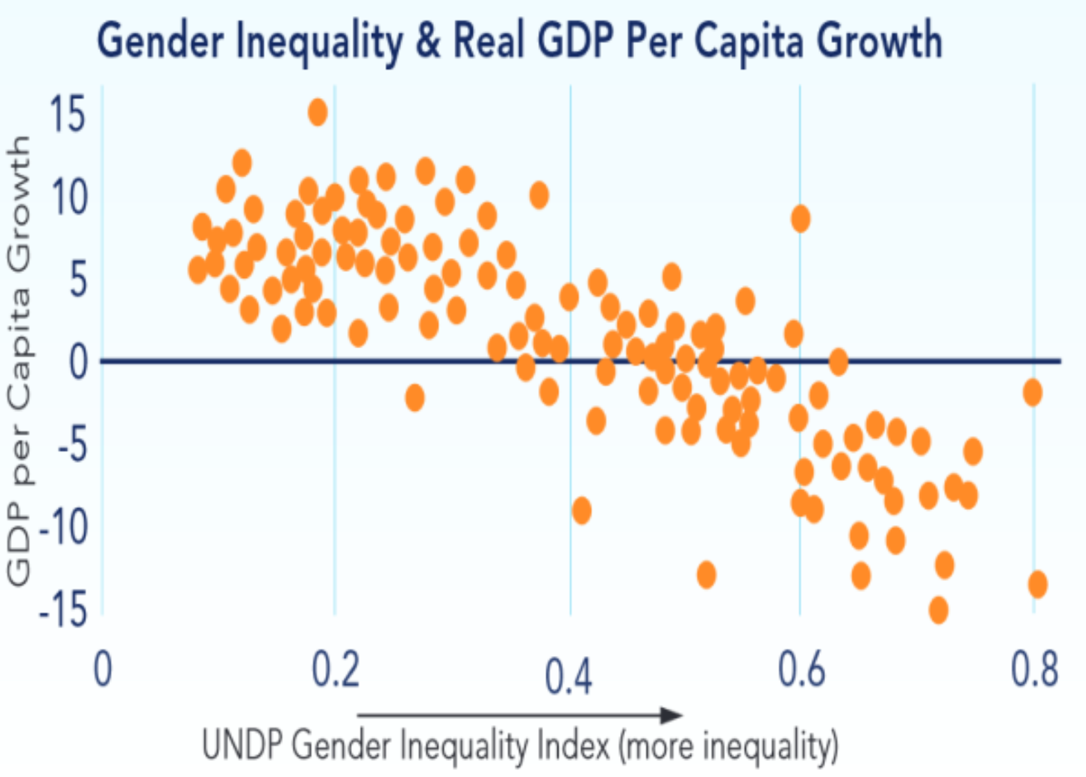

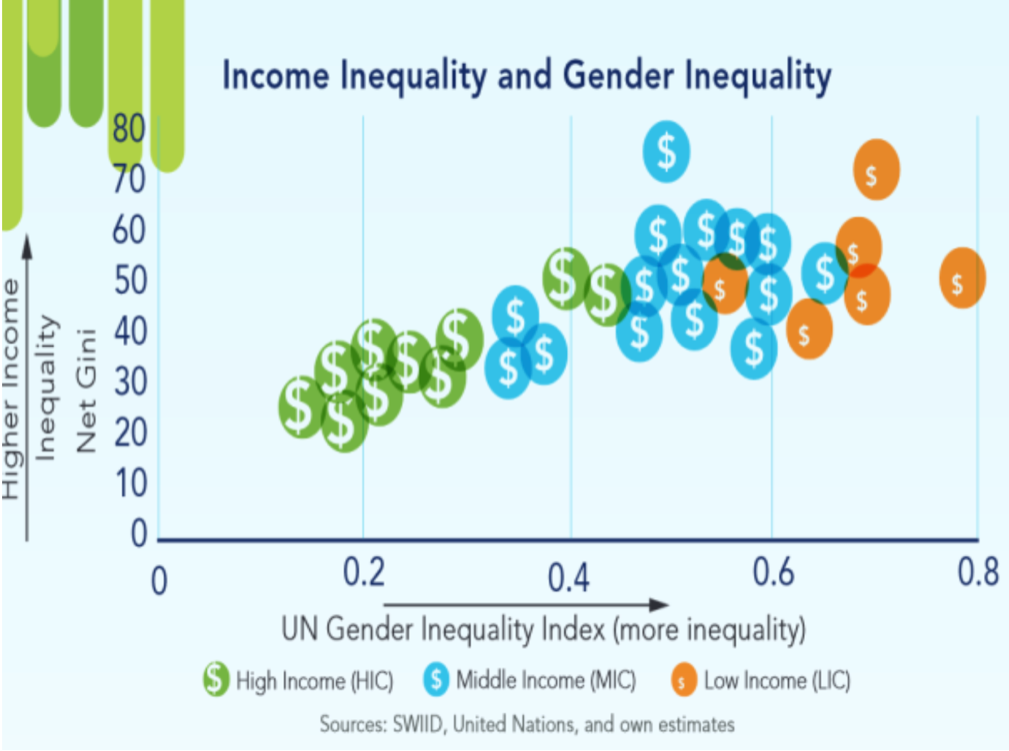

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) show how gender inequality is correlated with income inequality and real GDP per capita growth. Macroeconomic outcomes are affected by gender inequalities, and gender inequalities are influenced by macroeconomic policies. Clements (2019), for example, explores how gender inequality affects the UK labour market.

“The gender pay gap: low STEM participation, inaccessible labour markets and behaviour” – Clements, 2019

Clements, L. (2019) The gender pay gap: low STEM participation, inaccessible labour markets and behaviour, Cambridge Econometrics.

Nelson, J. A. (2006) Economics for Humans, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, ISBN: 9780226572024. Available on Google Books.

Uncertainty is intrinsic and pervasive in understanding economic behaviour. Knight (1921) distinguished quantifiable uncertainty as risks, in the sense of being amenable to a statistical analysis using historical or experimental data, and fundamental uncertainty, that is intrinsic and unknowable.

The recognition of fundamental uncertainty is a critical feature of Keynesian economics, which distinguishes it from neoclassical economics, and assumes that agents can characterise uncertain outcomes by well-defined probability distributions.

“Information Security: Lessons from Behavioural Economics” – Baddeley, 2011

“Uncertainties in macroeconomic assessments of low-carbon transition pathways – the case of the European iron and steel industry” – Bachner et al., 2020

Knight, F. H. (1921) Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, Boston, MA. Available on Archive.

Taleb, N. N. (2007) The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, Random House and Penguin Books, New York, ISBN:978-1-4000-6351-2. [Expanded 2nd ed. (2010) ISBN:978-0812973815].

Fontana G. (2009) Money, Uncertainty and Time, Psychology Press. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203503294

Taleb, N. N. (2010) The Bed of Procrustes: Philosophical and Practical Aphorisms, Random House, New York, ISBN:978-1-4000-6997-2. [Expanded 2nd ed. (2016) ISBN:978-0812982404].

Baddeley, M. (2011) Information Security: Lessons from Behavioural Economics, Workshop on the Economics of Information Security. PDF available here.

Correlation does not imply causation when interpreting statistical relationships between economic variables. This is especially problematic for investment and skilled-labour demand. Both are needed for production to take place, and must precede the goods & services produced and consumed. Yet this future consumption is the driver of the earlier production.

Proving evidence of causality is important in the econometric estimation of relationships. In the absence of expectations, temporal causality (i.e. one set of events occurring systematically after another set of (causal) events) may be sufficient proof. This is the basis of Granger’s Causality Test.

Unless variables are properly defined, errors in causation can be very damaging. Expansionary austerity policies, for example, appear to have been based on errors in methods leading to reverse causality between public-sector deficits and GDP growth.

Breuer, C. (2019) Expansionary Austerity and Reverse Causality: A Critique of the Conventional Approach, INET Working Paper.

In a monetary economy, supplies of goods and services are derived from demand. Suppliers aim to manage demand through pricing, advertising, offers and availability. In a free market, however, consumer and government demand drives the economic system.

Supply equals demand in accounting terms, but Say’s Law (supply creates its own demand) does not hold. However, supply must necessarily precede demand in time, so that suppliers must anticipate and envision demand in a trial and error process, having profound implications for economics. The supply-demand curves in elementary neoclassical economics are highly misleading and wrong.

“Towards a ‘New Economics’: Values, Resources, Money, Markets, Growth and Politics” – Barker, 2011

Barker, T. (2011) ‘Towards a ‘new economics’: values, resources, money, markets, growth and policy”, in Arestis, P. and Sawyer, M. (eds), New Economics as Mainstream Economics, Palgrave Macmillan. DOI:10.1057/9780230307681_2.

Demand and supply curves are a diagrammatic representation of equilibrium in neoclassical economics. These continuous curves, with the advanced mathematical form (with assumptions of continuity, constant returns to scale and representative agents) being Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models dominating macroeconomic literature, are misleading or wrong for many reasons.

1) Demand and supply cannot be continuous for indivisible goods and services, i.e. lumpy items such as vehicles. Only money makes real goods appear continuous and divisible.

2) The institutions involved, the location, and time are essential in understanding economic behaviour and outcomes. None are present in the diagrams.

3) Markets clear in many ways (e.g., prices, availability, stockbuilding, wastage, reallocation, rationing). Clearing through prices is unduly restrictive. Equilibrium through pricing is imaginary.

4) Supply and demand are not independent and they are uncertain.

5) In identifiable markets there are normally many goods and service, and many prices, with limited information about quality.

Production refers to economic activities, usually marketed but including government services, classified in the UN System of National Accounts. These activities (outputs) generally require inputs of land, capital, labour, energy and other goods and services using technical knowledge for their production.

Input-output tables show, for countries & regions, the inputs per unit of output for a specific period, usually a year. They are used in input-output models to allow for industrial structure and/or intermediate demand.

The production function is a neoclassical concept that is contested as bogus and immeasurable in new economics.

“Guide to Measuring Global Production” – UNECE, 2015

“Linking the developmental state to green economic growth” – Arestis et al., 2022

Goods and services are tangibles and activities that are assumed to benefit purchasers or users in terms of their needs or wants.

Products are goods and services classified by producing industries.

Commodities are groups of similar goods, usually raw materials and foods.

Replicated goods and services are items indistinguishable to the purchaser by location and time, e.g., multiple items on supermarket shelves or internet checkouts.

Goods and Services: Simple Examples in Economics – Gunner, n.d.

Economies of scale (including those of specialisation, networks, and over time) are pervasive in production and consumption. They are partly the result of the laws of physics (volumes increase faster than surface area as a body increases in size), but they also arise through sharing fixed resources.

Economies of scale allow substantial reductions in costs, hence, they are exploited if available and tend to dominate production. Constant returns to scale are by definition rare, but are chosen as an assumption in neoclassical equilibrium models to make them tractable.

“Returns to scale and regional growth: the static-dynamic Verdoorn law paradox revisited” – McCombie and Roberts, 2007

Verdoorn’s Law – Wikipedia

Specialisation – StudySmarter

McCombie, J. S. and Roberts, M. (2007) Returns to scale and regional growth: the static‐dynamic Verdoorn Law paradox revisited, Journal of Regional Science, 47, 179-208. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2007.00505.x

Productivity measures the efficiency of production in terms of its inputs of resources such as labour, capital, energy or materials. It is the input into a productive activity per unit of its output. The productivity of a national economy normally refers to its output (GDP in real terms) per unit of labour use (hours worked).

Technological progress has contributed to ongoing increases in national productivity. The slow-down in productivity growth since the Great Recession has been caused by changes in mix of production towards services, lower rates of investment, changes in the labour market weakening workers’ conditions, and low wage growth relative to output-price growth.

“Explaining, Restoring Low Productivity Growth in the UK” – Arestis and Peinado, 2018

“Productivity: Past, Present and Future Introduction” – Chadha, 2019

Arestis, P. and Peinado, P. (2018) Explaining, Restoring Low Productivity Growth in the UK, Challenge, 61:2, 120-132, DOI:10.1080/05775132.2018.1443988.

Chadha, J. S. (2019) Productivity: Past, Present and Future Introduction. National Institute Economic Review, 247:1, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/002795011924700109.

Energy demand is usually correlated to income and price, neglecting the effects of behavioural factors, the environment and the macro‐economy. However, even psychological studies from the 1990s show that monetary measures are not considered the only important factors in affecting energy demand and conservation.

Consumption patterns are dynamic and multidimensional, affected by behavioural, institutional, economic, policy, environmental and technological factors, that could lead to macro‐economic rebound effects or even backfire within the economy, as in case of internal combustion engine that enhanced the second industrial revolution.

“What psychology knows about energy conservation” – Stern, 1992

“The macroeconomic rebound effect and the UK economy” – Barker et al., 2007

“The macroeconomic rebound effect and the world economy” – Barker et al., 2009

Stern, P. C. (1992) What psychology knows about energy conservation, American Psychologist, 47:10, 1224‐1232. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.10.1224

Barker, T., Dagoumas, A. and Rubin, J. (2009) The macroeconomic rebound effect and the world economy, Energy Efficiency, 2:4, 411-427. DOI:10.1007/s12053-009-9053-y

Aggregation is a major problem in economics. Taleb, in The Bed of Procrustes (2010), summarizes the central problem: “we humans, facing limits of knowledge, and things we do not observe, the unseen and the unknown, resolve the tension by squeezing life and the world into crisp commoditized ideas”.

Economic theory deals with aggregates, such as the demand across consumers for a product (microeconomics), or total consumption in a national economy (macroeconomics). However, on further examination, there are vast numbers of products, consumers and firms in a complex dynamic network underlying these aggregates.

The National Accounts brings order to the data, but inevitably they omit hard-to-measure or immeasurable aspects of human, animal and ecosystem well being.

“Understanding aggregate growth: The ned for microeconomic evidence” – Haltiwanger, 2009

“Aggregation (econometrics)” – Stoker, 2010

Taleb, N. N. (2010) The Bed of Procrustes: Philosophical and Practical Aphorisms, Random House, New York, ISBN:978-1-4000-69 [2nd ed., 2016 ISBN:978-0812982404.97-2]

Economics requires assumptions about the composition of aggregates, such as products, consumers and producers, in a daily market. These aggregates are composed of many diverse goods, individuals or firms.

Humans and human institutions have agency, i.e. choice, and can be assumed to follow common rules of behaviour as consumers or producers. However, there is a crucial difference between assuming that all the agents are heterogeneous (perhaps following a normal or other distribution) or identical (representative of the average).

Diversity is an inherent feature of people and firms (e.g., age, culture, tastes, abilities, experience), and is essential for evolution and well being. However, the alternative assumption of identical representative agents makes modelling behaviour tractable and this assumption has become the basis of most neoclassical macroeconomic analysis, making it potentially misleading.

“Whom or What Does the Representative Individual Represent?” – Kirman, 1992

“Beyond DSGE Models: Toward an Empirically Based Macroeconomics” – Colander et al., 2009

Kirman, A. (1992) Whom or What Does the Representative Individual Represent?, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6:2, 7-36. Available on JSTOR.

Colander, D., Howitt, P., Kirman, A., Leijonhufvud, A. and Mehrling, P. (2008) Beyond DSGE Models: Toward an Empirically Based Macroeconomics, American Economic Review, 98:2, 236-40. DOI:10.1257/aer.98.2.236

The problem for economic theory and application is how to represent the heterogeneity inherent in the world.

One approach is to disaggregate into institutional sectors sharing common characteristics. For example, “industry” is disaggregated into sectors using common technologies (electricity) or producing closely related products (aircraft). Another approach is to use statistical distributions based on the properties of the population of the aggregate.

(See heterogeneous agents vs. representative agents above.)

Money is a resource with a set of characteristics that are embodied in different combinations of monetary assets (forms of money).

The main characteristics of money are: trustworthiness, divisibility, maintenance of value over location & time, limitation of supply, and convenience. These characteristics allow money to be used in accounting and recording of transactions and wealth, as well as allowing forms of money to be used as mediums of exchange and savings. Monetary assets include notes and coin, bank loans/deposits, credit and debit cards, and various government-backed and short-term bills of exchange.

Since commercial banks can generate loans if consumers or firms request them, the supply on money is endogenous to the monetary system.

“Endogenous money on 21st Century Keynesian economics” – Barker, 2010

Barker, T. (2010) “Endogenous money in 21st Century Keynesian economics”, in Arestis, P. and Sawyer, M. (eds), 21 Century Keynesian Economics, Palgrave Macmillan. Available on Academia.

Fontana, G. (2009) Money, Uncertainty and Time, Routledge. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203503294.

Skidelski, R. (2018) Money and Government: A Challenge to Mainstream Economics, Allen Lane, London. Available on Google Books.

Simmel, G. (1900) The Philosophy of Money. Description available on Wikipedia.

Integrality is the property of goods or services that make them indivisible if they are to be fit for purpose. In economics, one characteristic of money is that the monetary value of indivisible goods or services makes them conceptually divisible.

It is a basic problem in microeconomics that demand and supply is assumed continuous and divisible, when it is not, thus eliding monetary values and real quantities. This is a feature of economism – the tendency of economists to see the world in terms of demand and supply in equilibrium.

“Endogenous money on 21st Century Keynesian economics” – Barker, 2010

Barker, T. (2010) “Endogenous money in 21st Century Keynesian economics”, in Arestis, P. and Sawyer, M. (eds), 21 Century Keynesian Economics, Palgrave Macmillan. Available on Academia.

A monetary system is the dynamic interaction of institutions concerned with the provision and management of monetary assets designated as legal tender or otherwise regulated by the state. Today’s system of fiat money has as its main institutions: the Central Bank, commercial banks, the Ministry of Finance or Treasury, and the currency and bond markets.

Monetary assets are created by banks lending to customers, who then create more deposits or exchange the money for goods and services, so that others deposit the money and so on.

The Central Bank does not control the supply of money; instead it imposes conditions on the commercial banks, such as a requirement to hold reserves in the Central Bank. They are paid interest on those reserves, which is decided by the Central Bank (Banks’ Base Rate). The commercial banks must maintain a balance between lending and borrowing to remain solvent.

Epstein, G. (2019) What’s Wrong with Modern Money Theory? A Policy Critique, Palgrave Macmillan.

Financialisation is “… the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies.” (Epstein, 2005, p. 3). The financial sector is banking and finance, insurance, real estate, and auxiliary services.

If financialisation is the increase in the share of this sector in current GDP, the process is apparent in the UK (10% 1976 -> 20% 2008), France (10% -> 13%), Italy (4% -> 11%) and the USA (5% -> 9%). The UK is the most financialised large economy, led by London as a world financial centre. Even social care has seen widespread financialisation in the UK (IPPR, 2019).

The sector has grown through a process of regulatory capture, starting from the Thatcher-Reagan “big bang” deregulation 1979 onwards. The process culminated in the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, caused by unrestrained creation of new financial instruments, excessive leverage and systemic weakness in re-insurance against losses. These problems remain.

Source: IMF (2019)

“The finance curse: how the outsized power of the city of London makes Britain poorer” – Shaxson, 2018 (The Guardian)

“Who cares? Financialistion in social care” – The Progressive Policy Think Tank, 2019

“Financial effects in historic consumption and investment functions” – Stockhammer and Bengtsson, 2019

City Political Economy Research Centre

Financialisation, Economy, Society & Sustainable Development (FESSUD) Project. Co-ordinator: Malcolm Sawyer, Leeds University, FESSUD studies

Epstein, G. A. (2005) “Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy”, in G. A. Epstein (ed.), Financialization and the World Economy, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Cheltenham. pp. 3-16. Available on Google Books.

Christopherson, S., Martin, R. and Pollard, J. (2013) Financialisation: roots and repercussions, Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society, 6, 351-357. DOI:doi:10.1093/cjres/rst023.

Palley, T.I. (2013) Financialization: The Economics of Finance Capital Domination, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. Available on Google Books.

Sawyer, M. (2014) What is Financialization, International Journal of Political Economy, 42:4, 5-18. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2753/IJP0891-1916420401.

Van Der Zwan, N. (2014) Making Sense of Financialization, Socio-Economic Review, 12:1, 99-129. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwt020.

Christensen, J., Shaxson, N. and Wigan, D. (2016) The Finance Curse: Britain and the World Economy, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18:1, 255-269. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115612793.

Shaxson, N. (2018) The finance curse: How global finance is making us all poorer, The Bodley Head, London. Available on Google Books.

Blakeley, G. and Quilter-Pinner, H. (2019) Who Cares? The Financialisation Of Adult Social Care, Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). PDF available here.

Stockhammer, E. and Bengtsson, E. (2019) Financial effects in historic consumption and investment functions. Lund Papers in Economic History. General Issues, No. 2019:188. PDF available here.

Traditional finance relies on the principles of modern portfolio theory, such as the efficient market hypothesis, assuming that all investors are rational and all available information will be interpreted correctly by investors, banking institutions and decision makers. However, project decisions are affected by individual behaviour and the institutional framework.

There exist several biases that might affect investment decisions: anchoring, overconfidence, loss aversion, representativeness, aversion to ambiguity, endorsement effect. Capturing behavioural aspects as well as uncertainty, e.g. of energy systems, enables offsetting perfect foresight of optimization and equilibrium models.

“Behavioral issues in financing low carbon power plants” – Liang and Reiner, 2009

“The effects of the financial system and financial crises on global growth and the environment” – Anger-Kraavi and Barker, 2015

“Review of models for integrating renewable energy in the generation expansion planning” – Dagoumas and Koltsaklis, 2019

“Closing the green finance gap – a systems perspective” – Hafner et al., 2020

“Macro-economic and financial policies for sustainability and resilience” – Arestis, 2021

Liang, X. and Reiner, D. (2009) Behavioral issues in financing low carbon power plants, Energy Procedia, 1:1, 4495-4502. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2009.02.267.

Dagoumas, A.S. and Koltsaklis, N.E. (2019) Review of models for integrating renewable energy in the generation expansion planning, Applied Energy, 242, 1573‐1587. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.03.194.

Much of applied macroeconomics is about managing the economy by means of fiscal, monetary and regulatory economic policies. In new economics, all three types of policy should work together in a package depending on the problem to be addressed.

Within these broad types, specific economic instruments (e.g. the rate of VAT, the Central Bank’s base rate, or the carbon price floor) will have characteristics that should be taken into account when devising the policy package. For example, interest rate reductions combined with a fiscal stimulus to offset a sudden fall in aggregate demand, or a tax on fossil fuel to offset the rebound effects of an energy efficiency programme.

“Introduction to the special issue: Economic policies of the new thinking in economics” – Arestis and Sawyer, 2012

Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge

Arestis, P. and Sawyer, M. (2012) Introduction to the special issue: Economic policies of the new thinking in economics, International Review of Applied Economics, 26:2, 145-146. DOI:10.1080/02692171.2012.641766

A critical aspect of long-term economic policy is incentivising low-GHG and air-quality innovation and technological change. This can be done by fiscal policy, e.g. a carbon tax or an emissions-permit scheme, or through regulations improving energy-efficiency or reducing emissions of pollutants.

Historically, many innovations have come through government projects and direct support. Such investment may be crucial in large-scale, widespread transition to a decarbonised global economy.

“Modelling innovation and the macroeconomics of low-carbon transitions: theory, perspectives and practical use” – Mercure et al., 2019

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP), Bartlett, UCL

Barker, T., Crawford-Brown, D. (eds.) (2015) Decarbonising the World’s Economy: Assessing the Feasibility of Polices to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Imperial College Press. Available on Google Books.

Mazzucato, M. (2013) The Entrepreneurial State, Penguin Books, ISBN:9780141986104.

Mercure, J., Knobloch, F., Pollitt, H., Paroussos, L., Scrieciu, S.S. and Lewney, R. (2019) Modelling innovation and the macroeconomics of low-carbon transitions: theory, perspectives and practical use, Climate Policy, 19:8, 1019-1037, DOI:10.1080/14693062.2019.1617665.

It can be argued that economists who give advice to governments and business should have practical experience of economic activities.

As Keynes (1930) remarked “[the economic problem] should be a matter for specialists-like dentistry.” Just as dentists must have successful experience to qualify, so professional economists should have some experience of the economy, not just as consumers but as business people operating in markets.

If they understand money and business, surely they should also be successful, as Keynes was in his stock market operations.

Keynes, J. M. (1930) “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”, in Essays in Persuasion, 358-373. PDF available here.

Post-Keynesian economics treats the economy as a monetary phenomenon, with output, employment and investment driven by expected demand by consumers. Full employment and full capacity utilisation are not guaranteed. Uncertainty and lack of information dominate decision making. Economic behaviour is social and institutional, and not necessarily rational.

Unlike New Keynesianism, it rejects equilibrium and constrained optimisation of utility or profits as organising principles. Money is endogenous to the economic system and outcomes are path-dependent.

“Compare the perspectives of economics” – Society for Pluralist Economics

A Post-Keynesian reading list – Post-Keynesian Economics Society

“On the linkage between government expenditure and output: empirics of the Keynesian view versus Wagner’s law” – Arestis et al., 2021

Economism is the tendency of (neoclassical) economists to see the world in terms of:

- demand and supply operating in equilibrium,

- competitive markets, and

- rational, self-interested behaviour

When, instead, the world:

- is in flux,

- has markets restricted in location and time, with many non-price mechanisms for market clearing, and

- considers altruistic behaviour as a critical component of social life

Taken from James Kwak’s Economism:

In income:

1. Economism’s claim is that the minimum wage causes unemployment and harms poor people. The more likely reality is that the minimum wage has little impact on unemployment and reduces poverty.

2. Economism’s claim that people’s earnings are closely based on the value of their work. The more likely reality is earnings are very roughly related to productivity and highly dependent on bargaining power

3. Economism’s claim that reducing tax rates on labor causes people to work more, increasing economic growth. More likely reality is tax rates have a small affect on work, primarily for married women.

4. Economism’s claim that reducing tax rates on investments causes people to save more, increasing economic growth. More likely reality is savings rates are not affected by tax rates around current levels.

In healthcare:

5. Economism’s claim is that cost sharing [with insurance] causes people to make smarter choices, reducing waste and improving health. More likely reality is cost sharing causes people to spend less on all types of care, sometimes harming their health.

6. Economism’s claim is that competitive markets are the best way to give high-quality affordable healthcare. More likely reality is countries with universal government sponsored systems have lower costs and equal or better outcomes.

In financial markets:

7. Economism’s claim is that people only buy financial products that are good for them. More likely reality is many people make poor choices about complex products, such as option ARMs

8. Economism’s claim is that complex financial products improve the allocation of capital. More likely reality is that extreme complexity can produce excessive risk-taking and systemic instability

In international trade:

9. Economism’s claim is that international trade makes everyone better off. More likely reality is that international trade may benefit people on average, but make some people much worse off.

10. Economism’s claim is that free trade agreements contribute to overall prosperity. More likely reality is that some free trade agreements have less to do with free trade than with corporate rights.

Kwak, J. (2017) Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, ISBN: 1101871202, 9781101871201. Available on Google Books.