Date: Wednesday 8th March, 2023

Time: 09:00 – 17:00

Location: Downing College, Cambridge, UK.

On March 8th, 2023, we hosted a conference in Downing College, Cambridge, to explore policies that could help tackle the cost-of-living crisis – Is there a case for universal basic income (UBI)? Can debt-free sovereign money help mitigate the crisis?

The cost-of-living crisis refers to the fall in real disposable incomes, and it has affected us all to varying degrees – from food shortages and loss of welfare, to greater levels of societal division and poverty. The dysfunctionality in western economies has largely led to a situation where wage and work are no longer sufficient for income adequacy, and a new policy paradigm needed to deliver adequate household income and reduce national debt.

Over the duration of the conference, our speakers cover a wide range of topics, including:

- the macroeconomic implications of basic income

- the role of technology in reducing labour income

- the links between wealth and income

- the impacts of Brexit on living standards in the UK

- national solutions to the spiralling costs of living.

The conference began with welcomes from Dr Annela Anger-Kraavi (Chief Executive, CTNTE) and Professor Terry Barker (Founder, CTNTE), opening the conference by covering the aims and objectives of the day: to discuss potential solutions to the cost-of-living crisis, and to explore ideas, causes, and potential outcomes – from multiple perspectives and geopolitical approaches – with experts from academia, public and private sectors.

The toggle boxes below contain a summary of the talks provided by our speakers. To view the original event page, click here. To skip straight to the presentations, click here.

Social Program Reform to Cope with the Cost-of-Living Crisis: Mexico’s Approach

Dr Francisco Arias (Head of the Tax Policy Unit, Ministry of Finance, Mexico) opened the conference as our keynote speaker, and gives a presentation on Mexico’s approach to the cost-of-living crisis: social programme reform. Throughout Dr Arias’ talk, he explores the social policy outlook in Mexico, fair taxation for revenue growth, expenditure reorientation of social programs, and macro stability – including the positive economic impacts arising from an increase in minimum wage.

Dr Arias goes on to detail the reasoning behind Mexico’s tax policy reforms. They sought to close tax loopholes, eliminate regressive tax expenditures, and fight tax fraud. To do so, Mexico implemented a number of measures – digital economy tax reform, increased penalties for tax evasion, and the elimination of universal compensation and surveillance tax refunds. Dr Arias evidences how these measures, among others, have resulted in improvements to Mexico’s main revenue sources and VAT.

Dr Arias then describes Mexico’s social programs, and pro-worker policies, exploring the positive economic impacts of a program, established in 2019, that doubled minimum wage and halved VAT. He evidences how the increase in minimum wage attracted more people to the labour force, increasing employment without causing upwards pressures on inflation whilst preserving Mexico’s balance of public finance and macro stability.

Rethinking Income and Money: The Macroeconomics of Basic Income and Sovereign Money

Rethinking Income and Money: The Macroeconomics of Basic Income and Sovereign Money

Our next speaker, Geoff Crocker (Editor & Creator, Basic Income Forum), presented on the macroeconomics of basic income and sovereign money, as well as the need to rethink the concepts of income and money themselves.

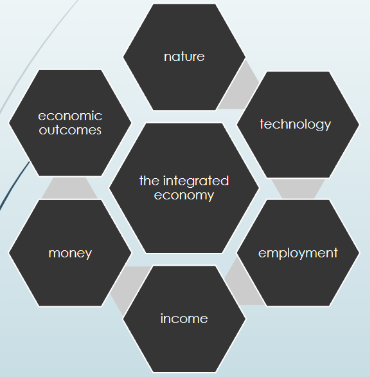

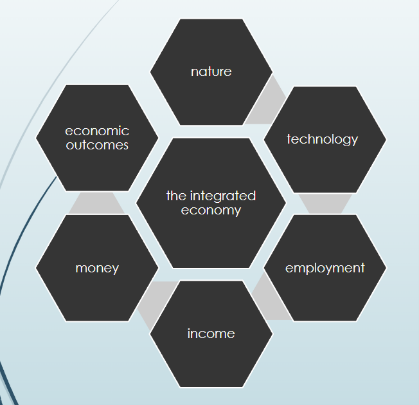

Geoff began his presentation with a call for an ‘Integrated Theory of Technology, Employment, Income and Money’ to incorporate technology into economic theory. He then moves on to discuss dysfunctionality within our current economic paradigm, and how it has led the UK to a place of inadequate incomes, excessive debt, and unbridled ecological damage. Following this, Geoff explores the hypothesis that automation is sucking income out of the economy, reducing aggregate labour income, and accumulating debt.

Geoff argues that we need a radical re-think and re-engineering of our current economic system – and this restructuring could incorporate a basic income and the use of debt-free sovereign money (DFSM). He states that DFSM, or the direct monetary funding of government spend, is the only way to deliver an adequate basic income at an affordable cost, being able get income to the people and debt out of the economy.

Geoff then presents on the case for basic income schemes in the UK, exploring five key benefits offered by the schemes:

- They can lead to increased social justice, and address inequalities within society.

- They represent the best welfare system, being less intrusive and less costly, with a higher uptake than means-tested benefits (they also do not come with unemployment or poverty traps).

- They break the link between income and (ever more) output, leading to less resource depletion and pollution.

- They enable “human flourishing” by allowing individuals a choice of lifestyle.

- They generate macroeconomic benefits by mitigating reduced income as a result of growing automation, removing debt from the economy (whilst avoiding austerity), and allowing for policy and philosophy to become less work-centric.

Geoff points out how a “pilot” UBI and DFSM was, essentially, delivered in the COVID economy through furlough schemes.

Furlough schemes paid £24k to three million people at a cost of £69 billion, and the Bank of England bought £875 billion of government debt (= debt-free sovereign money).

Macroeconomic Implications of a Basic Income: Modelling Basic Income in the UK

After the first recess, Chris Thoung (Director, Cambridge Econometrics) spoke on the macroeconomic implications of a basic income, presenting the results of a modelling analysis into how basic income schemes may operate in the UK. (You can read the report his presentation is based on here.)

Chris began by detailing the motivation behind the project. Social interest in UBI has seen a recent renewal, yet the macroeconomic dynamics of basic income have rarely been explored – particularly in regards to household income and expenditure effects, as well as labour supply (aka incentives to work). He then explains the research methodology adopted by him and his colleagues to model different policy scenarios, and their use of Cambridge Econometrics’ macroeconomic model, E3ME, to compare a ‘business as usual’ scenario against UBI policy scenarios.

Turning his attention to the results, Chris then explains how the Small-Scale Basic Income scenario showed neutral GDP impacts. The scenario saw slightly increased spending, a small increase in the number of jobs, and the potential for mild inflation. On the other hand, the Automation and DFSM Basic Income scenario (where basic income is used to return household incomes to baseline levels) indicated an adverse automation future, where widespread automation led to lost jobs and income, and the potential for mild inflation.

Chris closes his presentation summarising the wider impact of this work. The research suggests that any inflationary impacts of UBI are mild, and there are no obvious deleterious effects for an economy operating below capacity. However, the design of the scheme is crucially important. A widely automated future may erode household income and lead to deficient demand, but a basic income can sustain household income and DFSM appears stable in real-economy terms. Chris indicates that whilst implementing a basic income in the UK may, slightly, increase prices, the UK economy is able to absorb the (mild) increases in demand generated by the basic income schemes. In the short run, this shock is absorbed by higher capacity utilisation; in the long-run, productive capacity expands to match demand.

Technological Change and Growth Regimes: Assessing the Case for Universal Basic Income in an Era of Declining Labour Shares

Next up to speak was Dr Joe Chrisp (Research Associate, Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath) who presented the results of a research project into technological change and growth regimes, and the base for basic income in an era of declining labour shares. (You can read the report Joe’s presentation is based on here.)

Dr Chrisp begins his talk by explaining the three main motivations behind this research:

- To examine the evidence for claims that technology is responsible for declines in the labour share.

- To explore whether a comparative political economy perspective can explain cross-national differences.

- To relate these findings to an assessment of policy options and a UBI.

Dr Chrisp goes on to detail the factors behind the decline in the aggregate labour share across both OECD and Anglo-Saxon countries – globalisation (e.g., trade liberalisation and capital openness, or offshoring labour-intensive activities), the liberalisation of financial markets or labour markets, demographics, and technological change. He then explores the effects of technology on various economic indicators, such as the relative price of investment goods to consumption goods, as well as the effect of technology on the labour share (broken down by skill level), before discussing growth regimes and their corresponding effects.

Dr Chrisp then reviews the significance of a falling labour share – including increased inequality (and an increased need for fair distributive justice), threatened democratic policies, reduced household income and increased household debt – before finishing his presentation by offering a new way to structure the debate surrounding UBI. Joe argues that the question of how to fund UBI is basically a question of how to structure income tax (the means) so, when assuming we have the money to finance UBI, one could argue that there are “better” social policies we could invest in to stimulate the economy (the opportunity cost) – e.g., free childcare, increased Universal Credit, or greater financial support when purchasing a first home. And, even if it was possible to prevent technology from reducing the labour share, we need to speak about the structural future of our economy and ask some hard questions (structural) – e.g., could UBI be considered a way to ‘give up’ on structurally changing our economy? Even if UBIs can generate positive economic impacts in consumption-driven economies like the UK, what extent (if any) would this apply to export-driven economies?

Wealth, Income and Value

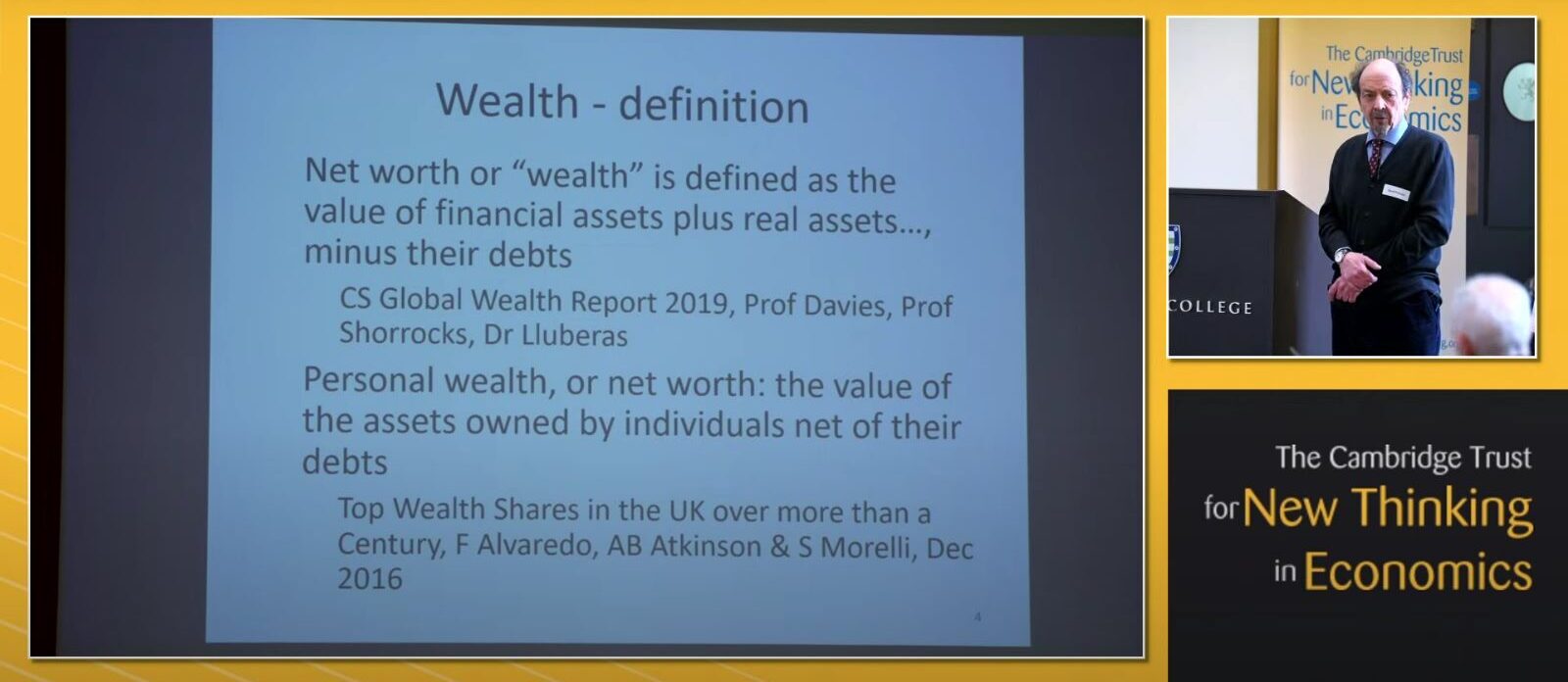

After lunch, David Fishman (independent researcher and consultant) discussed wealth, income and value. David offers an unequivocal value measure, explores the links between wealth, income and value, as well as their implications for a UBI.

David opens his talk by defining these three concepts – a surprisingly challenging task. Wealth is the value of financial assets, plus real assets, minus their debts. Personal wealth, or net worth, is the value of the assets owned by individuals net of their debts. David notes, however, that the definition of wealth incorporates “value” that (in this context) refers to the market price or marketable value – something that may appear circular, but just stands for monetary amount. Breaking wealth down further, David explains how non-financial wealth (or ‘real’ assets’), such as buildings and land, can be seen as wealth from the past. Whereas financial wealth, such as equities and bonds, can be seen as wealth from the future.

Turning his attention to value, David describes its three foundations: value; value-exchange; and, use-value. Similarly to wealth, the foundations of value can also be seen through the chronoscopic perspective of past, present, and future. He then explores the two triads of value and time, the valuing of assets, capital, and measures of valuation – illustrating the complexity involved when attempting to define intangible economic concepts – before turning his attention to how these concepts relate to UBI.

David presents a hypothetical basic income scheme in the UK that consists of an annual payment of £10k for everyone aged 20+ (with half this amount for children and teens). The annual cost of these hypothetical scheme is approximately £600 billion. The net cost, however, is approximately half of this. This £300 billion can be converted to a capital value of £3 trillion, equating to approximately £44k per capita. David acknowledges that, whilst this is a considerable amount of money, it needs to be put into perspective – total personal wealth in the UK is £16 trillion, so the UBI capital value of £3 trillion is less than 20% of this. Nevertheless, we need to ensure we funded a UBI in a way that does not burden future generations. In this regard, David argues that we could focus on the £8 trillion of wealth in the UK that is property and land (i.e., past wealth). He also points out how charities, trusts, and other not-for-profits are (largely) free of any fiscal burden due to tax breaks and subsidies, meaning that they have accumulated large quantities of wealth. He notes how the main site of Downing College itself (the location of our conference) pays £32k in business rates – the same amount as a small, basic restaurant in Cambridge – and its commercial enterprises pay no corporate tax due to offsets. In total, Downing College alone has approximately £230 million in declared net assets.

To close, David summarises how value under capitalism is social and the value of commodities is expressed in money – value, whether abstract or concrete, cannot appear directly, but can only arise through the exchange of money.

What impact is Brexit having on living standards?

Our next speaker to the stage is Dr Graham Gudgin (Honorary Research Associate, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge; Chief Economic Advisor, Policy Exchange), discussing the impact that Brexit has (or has not) has on living standards in the UK.

Dr Gudgin illustrates how, based on an aggregate measure, the living standards of people living in the UK have seen continued improvements, before discussing the trends exhibited by various economic indicators. Dr Gudgin then explores how different report measures or comparison groups can influence the trends observed when assessing the economic impact of Brexit in the UK. When comparing GDP performance among G7 countries, for example, the UK underperforms in both 2020 and 2022. However, if the USA is excluded, the UK actually outperforms compared to other G7 countries. Dr Gudgin goes on to reflect on the expansionary nature of US fiscal policy, and evidences how the UK’s economic performance is intermediate among the major world economies such France, Germany and Japan (UK manufacturing has even outperformed France and Germany since 2016).

Following this, Dr Gudgin speaks on how the CER Doppleganger effect – a weighted index of 22 comparator countries – shows many economies mimicking the decline in GDP seen in the UK in the years surrounding Brexit. He argues that such statistical artifacts have very little economic meaning (e.g., the CER’s weighted countries are not fair comparators for the UK) and should be withdrawn from current assessments of economic performance. Graham then details why he believes we should not expect business investments to continue on more recent trends (2009 – 2016), evidencing how our exports to the EU have recovered to pre-pandemic levels (and are greater than exports to non-EU countries) and how UK inflation is in-line with the levels experienced by other major economies.

Solving the cost-of-living crisis for the UK economy

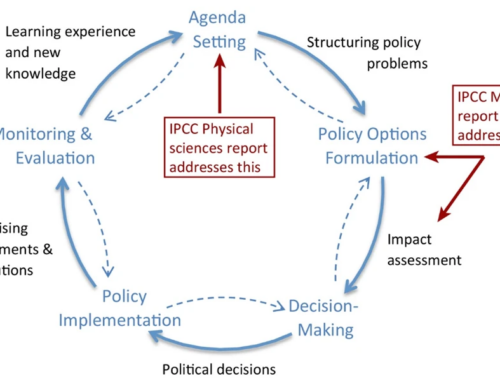

Closing our conference, Professor Terry Barker‘s (Founder, CTNTE) presentation summarised what the entire day is all about: how can we actually solve the cost-of-living crisis here in the UK? Professor Barker’s talk began by discussing the current economic system, before moving on to causes and effects of the crisis, and closing with solutions to the crisis that combine net-zero, equity, effectiveness, and efficiency (NZE3).

Professor Barker opens by outlining how under our present economic paradigm;

-

- Uncertainty is prevalent,

- Money is endogenous,

- Output, investment, employment, and trade are driven by effective demand,

- The economy is structured through institutions,

- Economic behaviour is social, institutional, and macro,

- Outcomes are path-dependent,

- The capitalist economy is an open system, with tendencies towards inequalities.

Professor Barker then compares key differences between Keynes’ and Keynesian economies, exploring the attitudes of Keynes’ (1936) General Theory, New Keynesian, and Space-Time Post-Keynesian, to the concepts of ethics and society, uncertainty, time and equilibrium, and analysis.

Following this, Professor Barker outlines some of the (innumerable) causes of the global cost-of-living crisis – including the reduced role of emerging-economies, the COVID pandemic, and the Russian invasion – before focusing on additional causes in the UK alone. He details how the spiralling cost-of-living in the UK has been further stimulated by the UK’s monetary and fiscal policy since 2010 (with low interest rates and inadequate demand management leading to low growth), Brexit undermining economic confidence, political division leading to poor policymakers and policy errors (e.g., Truss-Kwarteng), and the shock caused by unexpected and rapid rises in UK interest rates, leading to hoarding and increased volatility.

He then speaks on key effects of the current crisis – from increased poverty, morbidity, inequality, and division to a reduction in welfare, wellbeing, and self-respect – and how we could solve the UK cost-of-living crisis. Terry argues that we need to recognise that we are, effectively, at war and so require rapid, flexible and politically-acceptable solutions. New institutions, such as local assemblies that disperse new money via NZE3 projects, could be nationally-funding, regionally-monitored, and generate an environment of open information-sharing; or a new basic-needs price index, where interested parties agree on a co-ordinated and centralised supply to provide basic needs, could yield an economy of scale and be used as a reference in negotiations on wage increases. Professor Barker finishes his presentation by opening up the floor to fastidious debates, including discussions on the concepts of equilibrium and stability, post-banking crisis monetary policy, financial markets and assets, and the climate crisis.

Thank you.

Watch the livestream:

Opening Remarks (Dr Annela Anger-Kraavi & Professor Terry Barker): 08:08 – 18:32

- Dr Francisco Arias (Head of Tax Policy Unit, Ministry of Finance, Mexico): 18:33 – 45:44

- Geoff Crocker (Editor and Creator, Basic Income Forum): 45:44 – 1:04:04

- Joint Q&A: 1:04:03 – 1:44:00

Break

- Chris Thoung (Director, Cambridge Econometrics): 2:15:44 – 2:40:50

- Dr Joe Chrisp (Research Associate, Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath): 2:40:50 – 3:04:10

- Q&A (with guest Professor Nick Pearce (Director, Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath)): 3:04:10 – 3:33:33

Break

- David Fishman (Independent Researcher): 4:35:52 – 5:01:05

- Dr Graham Gudgin (Honorary Research Associate, Centre for Business Research, Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge; Chief Economic Advisor, Policy Exchange): 5:01:00 – 5:34:26

- Joint Q&A: 5:34:26 – 5:56:23

Break

- Professor Terry Barker (Founder, the Cambridge Trust for New Thinking in Economics) 6:24:00 – 7:06:14

Closing Remarks (Dr Annela Anger-Kraavi & Professor Terry Barker): 07:06:14 – 07:10:13

Or view directly on YouTube.

[]

View the presentations:

Dr Francisco Arias:

Social Programs Reform to Cope with the Cost-of-Living Crisis: Mexico’s Approach .

Geoff Crocker:

Rethinking Income and Money: The Macroeconomics of Basic Income and Sovereign Money

Chris Thoung:

Macroeconomic Implications of a Basic Income .

Dr Joe Chrisp:

Technological Change and Growth Regimes

David Fishman:

Wealth, Income and Value .

Graham Gudgin:

What Impact is Brexit Having on Living Standards?

Professor Terry Barker:

Solving the cost-of-living crisis for the UK economy

Learn more about our speakers: