Date: Wednesday 15th May, 2024

Location: Trinity Hall, Cambridge, UK

On May 15th, 2024, we hosted a workshop in Trinity Hall, Cambridge, for an open discussion about the implementation barriers to achieving net zero.

Currently, there is a lot of push back from various groups of society due to the increasing number of regulations, as well as increases in the cost-of-living due to climate measures. At the same time, there is a shortage of skilled labour to effectively implement climate measures. Together, these factors threaten our ability to achieve net zero.

The workshop was an open discussion about the implementation barriers to net zero in light of the current economic, social, and political pressures, and what exactly is needed to overcome them.

It revolved around two main topics: policy implementation and knowledge barriers, and practical obstacles. Overall, the main conclusions from the workshop were:

- Building trust among all stakeholders involved in the transition to low-carbon societies, including listening to those “stuck” in the process, is essential to achieve climate goals

- Transforming the current negative narrative surrounding climate change into a positive narrative to rebut counterarguments to climate action will be critical to achieve a successful transformation

- Explaining and sharing the benefits of climate mitigation, such as a reduction in air pollution, can be a highly successful strategy to engage those indifferent or opposed to climate action.

The toggle boxes below contain a summary of the discussions that occurred throughout the conference. To view the original event page, click here.

Communication needs to be clear. Policy makers and researchers typically speak in different languages, and the benefits of a fossil free energy system are rarely articulated. The barriers to change get more intense the closer it gets to the dining table. It is possible to electrify and decarbonise electricity, but when looking at, e.g., barriers to transport/retrofitting homes, it becomes personal – and these human barriers are the key ones that can become levers for arguments of counter-change.

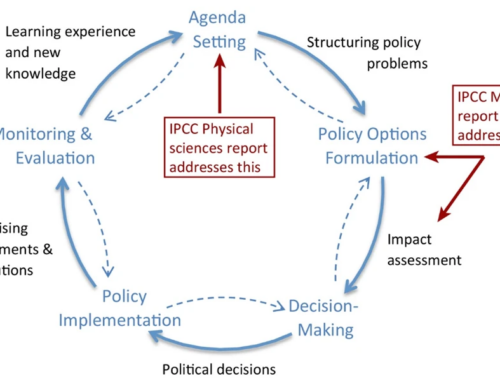

In the IPCC, there is a need for climate scenarios to address national policy-relevant questions. However, models chosen through this process are unable to capture flexibility, renewables’ penetration, system costs, etc. (particularly in short-term) and standard scenarios assume a global single carbon price to minimise policy costs (despite no single global carbon price). Climate models commonly use a shadow carbon price and underestimate the actual risks and damage costs, as well as the costs of transitioning to NZ. However, should intergenerational equity be used, then every mitigative measure taken today pays off.

The question asked generally determines the model used, and different models can provide different answers to the same question depending on what the model represents. Models cannot account for many factors (e.g., equity) and capture historical trends in, e.g., technology diffusion, that may not apply to future. Greater transparency is needed over model capabilities and outputs. It was emphasised that the point of modelling is not to provide an answer, but to draw out a narrative that if you push on this specific lever, it will likely draw out these effects. Modellers may be cautious in presenting what modelling can do as it gets lost between who asks the question and the actual policy. Policymakers expect a single answer, leading to the use of optimisation models and the settings of constraints. Instead, questions should be more nuanced and ask for 3-4 potential pathways to NZ, or policymakers should work with modellers to test specific policies and the routes/technology they bring about. However, it somehow needs to be explained why it is good to have multiple scenarios, and why a single answer cannot be provided.

The Summary for Policymakers is the main communication tool of each IPCC Working Group, but it is written in measured, nuanced, and calibrated language making it somewhat impenetrable and results may be misinterpreted. May also result in policymakers struggling to act. An IPCC weakness is only holding dialogue sessions at the end. Should this dialogue happen halfway though, it would make it easier to resolve any issues or miscommunications between policymakers and academics.

Researchers must be careful not to overpromote what markets can do when there is no effective global market for carbon. Governments need to have justification for climate action, and currently the economic price is the most suitable option. The price mechanism is the underlying and maybe the smallest common denominator of the whole debate. The worst climate impacts will largely occur in developing countries, so European markets would not reflect this. The question of who pays is often dismissed. The free market was meant to solve such issues, however, who pays is often at the core of the UNFCCC discussions. A counterargument is that humanity has already paid, and a narrative change is needed to refute misguided delays caused by payment conversations. The example of “reverse war planning” could be used: where countries pay for wars for years afterwards, there is a need to pay for climate adaptation and recovery now as even limiting global warming to 1.5°C will not come without loss and damage.

Carbon price is reductionist, does not accommodate alternative factors (e.g., air pollution or energy security) and is only useful if there is already an established political consensus surrounding the issue. It was argued that a simple CBA should not be used assessing climate change impacts for the entire world as there are many different actors with different value judgments. If there is a move towards more community-based decision-making models, the weight of climate mitigation is reduced in decision making if it is combined with other issues (e.g., noise).

The most vulnerable in society find it difficult to conceptualise or care about future climate impacts compared to immediate problems. However, shifting the narrative closer to home – such as by promoting the public health effects (e.g., benefits of reduced air pollution) – can become a key driver for climate action. The climate crisis can be seen as a health issue, and there were suggestions that achieving NZ could be delt with in the same way by policy. The benefits should be tangible. The key message being that climate action is good for you, your family, your country, etc.

Economics and economic thinking can provide poor advice, may be too central to the discussions on how to limit climate action, and give the allusion that things are possible when they are not. The need to change the entire economic paradigm so it lines up with climate decisions was suggested, as well as the need for better economics that underly IPCC work, or to just make climate decisions and let economists catch up. The entire institutional framework (e.g., UNFCCC, treasuries) is not set up for making climate decisions. An alternative way of thinking is that instead of focusing on an entire visionary world, to break it down into sectors.

Politicians are the ones who have to take the risk when implementing policy. They are time-constrained and need to be emboldened. However, the implementation, assessment, and progression of climate policies are still relatively new concepts.

The gap between societal risk and finance risk needs to be bridged. There are two different constructs of risk (social and financial), when the financial world realises that we are heading towards something, they will reprice risk very quickly. There are no collective discussions on what is going to happen when finance reprices societal risk. Fossil fuel companies are trying to make societal risk and financial risk the same as it is in their best interest. They can promote the fact that energy is needed forever, societal risk is ignored.

Another challenge discussed was how there are large clusters of industry (particularly in the UK) where a lot of energy is wasted, e.g., despite district heating being a well-known concept. There is a disentanglement of skills, a lack of skill capacity and a lack of interdisciplinary communication. There is not necessarily a skill shortage. Regarding heat pumps, there are enough engineers should they be convinced to switch from the fossil industry. There is a misperception of complexity, and the hierarchy of interventions must be explored. Should the technology grow, then governments/industry will need to consider the skills and begin educational initiatives. Infrastructure barriers discussed included the transportation of energy (e.g., solar and wind from West to East), grid connectivity, as well as institutional inertia. All actors must adhere to strict routines and structures that are difficult to change, and vested interests, such as political opportunities or “well-funded losers” who do not want to reduce emissions, may undermine climate science.

Public support for certain technologies (e.g., heat pumps) has been steadily increasing and a significant reduction in the cost has made them far more competitive, acting as both an economic and financial driver. To reduce resistance in large parts of society, if the social climate funds are properly marketed, it can act as a strong tool to explain to poorer parts of society that they will not be left behind (e.g., France financing the installation of heat pumps in the lowest income households). The benefit of high climate ambitions, such as the 1.5°C target, is that once it is put in public awareness, people will attempt to achieve it (e.g., the Brazilian parliament’s mission to 1.5°C). If it is taken seriously at a political level, then the elements that are needed to achieve it and plan for it can be mobilised (e.g., need to take CO2 out of the atmosphere, more than what would happen naturally, after we achieve neutrality).

It is difficult to push ambitious targets in, e.g., developing countries when they see reversals in the financial markets (e.g., developed nations reneging or underachieving on climate targets, despite having far more resources than developing nations). As well as the notion of a “just transition” beginning to be used as an excuse to delay climate action, rather than facilitate dialogue. Another cause for concern is related to the uncertainty within global politics. If mitigative action is considered Paris aligned, then there is an automatic assumption that it solves the climate problem and there is less focus on adaptation. It was discussed whether NDCs should be turned into transition plans, or whether future NDCs should be used as investment or sustainable development plans. However, it was noted that – as NDCs are every five years – a country would still need to have a long-term strategy (LTS) containing a pathway to NZ CO2. NDCs should be framed by LTS.